Research interests: Tracing the footsteps of Dr. Jose Rizal, Philippine American Writers and Artists, Inc. (PAWA), Filipino Book Festival

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Friday, February 18, 2011

Where did Dr. José Rizal write his famous novel: Noli me tángere?

Dr. José Rizal started writing his novel Noli me tangere in Spain and finished up the last chapters in Germany.

When did he have the time to write? It was 1885. He just successfully completed his Philosophy and Letters course work at the Universidad Central de Madrid. He was also completing his medical degree at the Medical College of San Marcos. He had a very busy schedule, but Rizal always always prioritized his hours. He made sure that he attended events of interest at the Ateneo de Madrid. Rizal's thoughts were already venturing into writing a novel about the Philippine condition. The idea was just percolating in his mind. With his enriched exposure at the Ateneo de Madrid his writing plans like a bottle of Champagne, begin to bubble to the surface with particular excitement as he met and interacted with several authors of the period.

At the Ateneo, de Madrid he was exposed to celebrated scholars, authors, literary celebrities, as well as political figures (where he met Prince Bismarck of Bavaria) through lectures, interviews, tertulias, drinking bouts, fabulous dinners, and theater and cultural performances.

Just to give readers a sense of my visit at Ateneo de Madrid in July 2007, I attended the following events:

Just to give readers a sense of my visit at Ateneo de Madrid in July 2007, I attended the following events:

|

| Madrid's Ateneo-- Rizal's favorite |

- A sculpture exhibit by Paraula

- A lecture on writing the historical novel: Laura Lopez and Mar Tomas

- The Short Story, Rolando Sanchez Mejias

- The Classics: Melcion Mateu

- Initiation into poetry: Marta Salinas

- Cinema, I saw a Barcelona movie

- Culture, I attended a fashion show. OK. not really high culture, I admit.

Calle Pizarro 15, formerly Pizarro 13, 2nd floor. (I know I took a picture of this place. I have to dig up my files and attach it later.)

He lived here from August of 1883 to September 1885. The flat was convenient because of its proximity to the Facultad de Filosofia y Letras. He was rooming with Ceferino de Leon and Julio Llorente. However, on 30 July, 1885, Rizal wrote his parents that Julio got married and moved out, while Ceferino left for Galicia in Northern Spain. So Jose Rizal, for the very first time had the flat all to himself. This is where he finally and seriously sat down to write the Noli.

At certain intervals, he would invite his friends over and they would gather around Rizal for a reading. Once, he read his draft chapter on Sisa. Not a single eye was dry. Felix Pardo de Tavera, a medical student and a younger brother of Trinidad, incredulously asked: "Is this true?" Rizal replied: "All I had written here actually happened."

Soon after Rizal got his medical degree he proceeded to Heidelberg Germany to train in Opthalmology with the noted eye specialist, Dr. Becker. However, he chose to stay with a German family several miles away in the village of Wilhelmsfeld. In the vicarage house of Pastor Karl Ullmer, he wrote the last final chapters of Noli me tangere.

Schreisheimer Hof is an inn near Pastor Karl Ullmer's vicarage house, Wilhelmsfeld, Heidelberg, Germany. It was at this inn where Rizal and Pastor Ullmer met with a Catholic priest. They spent the afternoon discussing about their respective Catholic and Protestant religions. Rizal learned a lot about regligious tolerance during their discussions.

|

| Schreisheimer Hof, an inn near Pastor Karl Ullmer's vicarage house, Wilhelmsfeld, Heidelberg, Germany |

Rizal sent the first copy to Blumentritt. The second was to Pastor Ullmer. Ullmer's great grandsons, Fritz and Hans Hack donated their family copy to the Philippine Government in 1961 at Rizal's Centenary Birthday celebration.

|

| Leoncio Lopez Rizal standing between Fritz Hack and Hans Hack of Wilhelmsfeld, Germany. 1961. |

Tuesday, February 1, 2011

Dr. José Rizal's annotation of Antonio Morga's "Historical Events of the Philippines".1609.

In 1889-1890, Dr. José Rizal spent several months in London first, to do his historical research on pre-colonial Philippines and second, to improve his English language skills.

He lived as a boarder with the Beckett family on 37 Chalcot Crescent, Primrose Hill, Camden town, Greater London. Today, if you visit London, you will see a Rizal plaque on this building's façade. It announces proudly: Dr. Jose Rizal. 1861-1896, Writer, and National Hero of the Philippines lived here.

Rizal had a burning desire to know exactly the conditions of the Philippines when the Spaniards came ashore to the islands. His theory was the country was economically self-sufficient and prosperous. Rizal entertained the idea that it had a lively and vigorous community enriched with the collective and sensitive art and culture of the native population. He believed the conquest of the Spaniards contributed in part to the decline of the Philippine's rich tradition and culture.

In order to support this argument, he had to find out a credible account of the Philippines before and at the initial Spanish encounter. According to Dr. Ferdinand Blumentritt, the noted Filipinologist, and Rizal's friend, the Spanish historian Dr. Antonio Morga wrote Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas which was published in Mexico in 1609. Many scholars considered this history of the Philippines a much better and honest description of the conditions in the country pertaining to the Spanish conquest.

Morga writes on his dedication page: ....this small book ....is a faithful narrative, devoid of any artifice and ornament....regarding the discovery, conquest and conversion of the Philippine Islands, together with the various events in which they have taken part...specifically describing their original condition...

Rizal spent his entire stay in that fog-draped city of London at the British Museum's reading room. He laboriously sifted, weighed, evaluated, each and every proof he could find in books, manuscripts, documents and other records from the vast British Museum's Filipiniana Collection. Having found Morga's book, he laboriously hand-copied the whole 351 pages of the Sucesos. Of course he had to. The Xerox copier and digital scanner were about 150 years yet toward the future.

Rizal proceeded to annotate every chapter of the Sucesos. It's a highly interesting and informative volume. In Chapter One alone, I note Rizal's footnotes ran over three-fourths up the pages (pp 4, 5). Like a brain surgeon examining a monitor, it's as if we are privy to an image of Rizal's brain and how it worked. Nothing but nada escaped his beagle eyes. He annotated even Morga's typographical errors. He commented on every statement that could be nuanced in Filipino cultural practices. For example, on page 248 Morga describes the culinary art of the ancient Filipinos by recording: ...They prefer to eat salt fish which begin to decompose and smell. Rizal's footnotes reads: This is another preoccupation of the Spaniards who, like any other nation in the matter of food, loathe that to which they are not accustomed or is unknown to them...... The fish that Morga mentions does not taste better when it is beginning to rot; all on the contrary: it is bagoong, and all those who have eaten it and tasted it know that it is not or ought not to be rotten.

The value of this work is immeasurable because Rizal provided the readers with such an array of rich societal and cultural footnotes with complete scholarly referenced resources and full citations. Each chapter is sufficiently and authentically annotated regarding the Philippines in ancient times. Sad to say, many students of Philippine history are unfamiliar with Rizal's annotated Historical Events of the Philippine Islands by Antonio Morga. This book is available in English published by the National Historical Institute, Manila, 1990.

I say to the serious Rizal scholar: Get thee to the "Sucesos annotated by Rizal." Your literary appetite will be whetted with juicy cultural episodes in italics penned by our national hero.

I suggest to the organizers of the forthcoming San Francisco Filipino American International Book Festival, scheduled to be held on the 1st and 2nd of October, 2011, that this precious volume be made available among the book exhibits.

He lived as a boarder with the Beckett family on 37 Chalcot Crescent, Primrose Hill, Camden town, Greater London. Today, if you visit London, you will see a Rizal plaque on this building's façade. It announces proudly: Dr. Jose Rizal. 1861-1896, Writer, and National Hero of the Philippines lived here.

Rizal had a burning desire to know exactly the conditions of the Philippines when the Spaniards came ashore to the islands. His theory was the country was economically self-sufficient and prosperous. Rizal entertained the idea that it had a lively and vigorous community enriched with the collective and sensitive art and culture of the native population. He believed the conquest of the Spaniards contributed in part to the decline of the Philippine's rich tradition and culture.

In order to support this argument, he had to find out a credible account of the Philippines before and at the initial Spanish encounter. According to Dr. Ferdinand Blumentritt, the noted Filipinologist, and Rizal's friend, the Spanish historian Dr. Antonio Morga wrote Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas which was published in Mexico in 1609. Many scholars considered this history of the Philippines a much better and honest description of the conditions in the country pertaining to the Spanish conquest.

Morga writes on his dedication page: ....this small book ....is a faithful narrative, devoid of any artifice and ornament....regarding the discovery, conquest and conversion of the Philippine Islands, together with the various events in which they have taken part...specifically describing their original condition...

Rizal spent his entire stay in that fog-draped city of London at the British Museum's reading room. He laboriously sifted, weighed, evaluated, each and every proof he could find in books, manuscripts, documents and other records from the vast British Museum's Filipiniana Collection. Having found Morga's book, he laboriously hand-copied the whole 351 pages of the Sucesos. Of course he had to. The Xerox copier and digital scanner were about 150 years yet toward the future.

Rizal proceeded to annotate every chapter of the Sucesos. It's a highly interesting and informative volume. In Chapter One alone, I note Rizal's footnotes ran over three-fourths up the pages (pp 4, 5). Like a brain surgeon examining a monitor, it's as if we are privy to an image of Rizal's brain and how it worked. Nothing but nada escaped his beagle eyes. He annotated even Morga's typographical errors. He commented on every statement that could be nuanced in Filipino cultural practices. For example, on page 248 Morga describes the culinary art of the ancient Filipinos by recording: ...They prefer to eat salt fish which begin to decompose and smell. Rizal's footnotes reads: This is another preoccupation of the Spaniards who, like any other nation in the matter of food, loathe that to which they are not accustomed or is unknown to them...... The fish that Morga mentions does not taste better when it is beginning to rot; all on the contrary: it is bagoong, and all those who have eaten it and tasted it know that it is not or ought not to be rotten.

The value of this work is immeasurable because Rizal provided the readers with such an array of rich societal and cultural footnotes with complete scholarly referenced resources and full citations. Each chapter is sufficiently and authentically annotated regarding the Philippines in ancient times. Sad to say, many students of Philippine history are unfamiliar with Rizal's annotated Historical Events of the Philippine Islands by Antonio Morga. This book is available in English published by the National Historical Institute, Manila, 1990.

I say to the serious Rizal scholar: Get thee to the "Sucesos annotated by Rizal." Your literary appetite will be whetted with juicy cultural episodes in italics penned by our national hero.

I suggest to the organizers of the forthcoming San Francisco Filipino American International Book Festival, scheduled to be held on the 1st and 2nd of October, 2011, that this precious volume be made available among the book exhibits.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

José Rizal's Books: Personal Library

The Philippine national hero, Dr. José Rizal had such a great attachment to his personal books. He resented the fact that while a student in Madrid, he learned from Paciano that one book in his Calamba collection was borrowed by a civil servant. He of course knew that when someone borrows a book, that item will never find its way back again on his sagging library shelves.

Let's take a peek at his personal library. among them are:

Let's take a peek at his personal library. among them are:

- The Count of Monte Cristo, Alexander Dumas, Spanish version.

- Travels in the Philippines, Fedor Jagor

- Guilliver's Travels, Jonathan Swift, in English.

- Lives of the Presidents of the United States-from Washington to Johnson. Deluxe, Morocco bound leather, gilt edge and illustrated copy.

- A History of the US Presidents, from Washington to Cleveland (used copy).

- A History of the English Revolution: A Comparison of the Romans and the Teutons.

- The Wandering Jew. Eugene Sue (used copy).

- Florante at Laura by Francisco Balagtas. He carried this volume in his breast pocket everywhere he went.

Saturday, January 1, 2011

Contextual Analysis: José Rizal's last letters to Blumentritt and to his family

wnadwritten Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Dr. José Rizal, age 35, prior to his execution in 1896

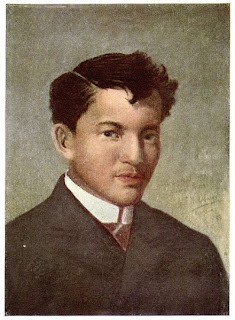

José Rizal, 18, University of Santo Tomas, Manila

|

| José Rizal, 20, Madrid, by Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, oil on canvas, 1883 |

You must read my (31st December, 2010) previous blog to make sense of what follows in this blog.

In this blog, I analyze the trigger words in the letters José Rizal wrote on 29th and 30th December, 1896, (see previous blog) that made him face his Maker peacefully, resignedly, and in tranquillity on his last two days on earth. I also included in the analysis his last thoughts (poem) written on the eve of the 30th, while waiting for the hour of his dawn execution, now known as the famous poem, Last Farewell.

I use the sociological research method called Contextual Ethnography where in one section, I tally a count: the number of times a word is used. On the second section, I gather the contextual meaning. The first section is what I will call the "Id" or the "personalized "I. This is Rizal's own frame of mind at that point in time. The second section is what I call the "Receiver." This is how his words are received and its meaning socially constructed by the circumstances and events of the time.

Caveat: I analyzed only the trigger words that bring out Rizal's sorrowful mood in braving his anxiety and impending doom. In other words, I could have analyzed separately the happy words that manifested joy and happiness, but that will be contrary to my present objective.

Analysis of Trigger Word Count: Contextual Ethnography of Rizal's Letters.

I. Trigger words/ number of times used

- DIE/28

- FAREWELL/7

- PEACE, HARMONY/6

Id. (Personal). As we can clearly discern, Rizal's frame of mind is fixated on his premature dying, as evidenced by the unusually high number count (28 times) of the following words: die, shot, death, martyrdom, sleep eternal, eternal rest, final rest, last, in my memory, premature end. Rizal reiterates his Farewell seven times: Twice in a letter to his father. To his brothers and sisters he talked of peace and harmony; he anticipated the severe burden his death will bring to Paciano.

(Receiver's Contextual Clue). The impending doom of his execution is felt strongly by the family, sympathizers, supporters, and friends. There is deep apprehension and resentment because the political time was wrought with danger and rebellion. There clearly was no sense of justice during his mock trial. But the message of the colonial government was-- Rizal will serve as an example to this rebellious colony. Blumentritt was visibly affected. When he received the farewell letter and his friend's book, he broke down crying. The book was an anthology of German poems which Blumentritt himself in the past had sent to his friend in Dapitan, and which Rizal had provided with comments and marginal notes.

II. Trigger words/ number of times used

- FORGIVE/4

- GRAVE/4

- PAIN/4

- REGRET/4

- WEEP/4

Id. (Personal). Rizal forgave his transgressors. He talked about the graveyard and the pain he brought to his family and friends, He regretted the pain suffered and brought against those close to him and those he loved. He enjoined them not to weep for him, but to weep instead for the poor country. He made a particular memorable metaphor in his letter to Paciano: the fruit is bitter because of the conditions, not because of the nature of the fruit. He was still thinking that the end of his life was bitter, but the bitterness was caused by the conditions of the colonial society. Rizal envisioned a people with dignity and pride with no regrets. He goes to his grave with no regrets for championing human dignity ( in today's lingo--of championing human rights).

(Receiver's Contextual Clue). Rizal will be shot in the morning, he will be gone, but his relatives and friends will still be there, a colonized oppressed people stripped of their human dignity while the friars were still dominating and controlling the government, the economy, the society, and the lives and deaths of the people. Rizal gave specific last dying instructions: no anniversary celebrations of his death. However, Philippine society and custom developed a different idea. In the Philippines we give bigger celebrations of the Pagkamatay (death anniversary: 30 December) instead of his birthday (19 June).

III. Trigger words/ number of times used

- BATTLEFIELD/3BREATH/3CONSCIENCE/3STRUGGLE/3

Id. (Personal). In his last farewell poem, he envisions struggles in battlefields thirce. This shows the conditions of his immediate environs at the time of writing: a virtual battlefield where he takes a full breath, and with his conscience remain clear as he struggles though the din.

(Receiver's Contextual Clue)

When the receivers read the battlefield metaphor, we must remember that in 1896, the Spanish Inquisition was still an immediate threat. During the execution, on the 30th of December, the atmosphere of the Bagumbayan crowd was likened to a battlefield. At another battlefield level, I introduce in context, an Auto da Fé: the execution procession for Catholic heretics (a circus-like event attended by all) to the Puerta del Sol, right on Plaza Mayor, Madrid led by the monarchy. This is why on the 30th of December 1896, the whole Spanish colonial administration, Spanish officials, and lay community came. Not watching the Auto da Fé was suspect. Hence, omission to witness Rizal's execution at Bagumbayan meant danger. While the Filipinos saw the execution in enraged silence, the Spanish ladies waved their handkerchief, as if witnessing a corrida, and the men applauded, shouting Viva España!

IV. Trigger words/ number of times used

- CONSOLE, PITY/2

- DREAM/2

- GLOOMY/2

- LAST/ IN MY MEMORY/2

- LONELY, FORLORN/2

- REDEMPTION/2

- SACRIFICE/2

Id. (Personal). Rizal consoles his family; he recalls his childhood dreams; and asked them to pity the lonely and forlorn Josephine Bracken. In his last moments. He used the word last twice. We feel his agony. Did he feel crucified? We don't know for sure, but I would hazard a guess he was feeling Messianic (my Catholic family will disown me for this blasphemy) since he used the word redemption and sacrifice twice. (I'll come to this later. See my Post Script at the bottom).

(Receiver's Contextual Clue)

His family clearly sees the end of his short life closing in as they contemplate the stirring emotions welling in their hearts.

V. Trigger words/ number of times used

- RESIGNED/1

- REST/1

- REGARDS/1

- THANKS/1

Id. (Personal). Finally Rizal is resigned to his death sentence. Now he is rested and calm. He sends his final regards to parents, brothers and sisters and to his bosom friend Blumentritt. Never think ill of me he writes. He feels eternal rest is sufferable and gives thanks that he has endured. He begins to write farewell to his very beloved mother: Doña Teodora Alonso, but words fail him. He just signed the letter and wrote the date and time at that very moment in Fort Santiago. To sister Trinidad, he hands over an alcohol lamp as a remembrance whispering in English: There's something inside.". In that alcohol lamp was found rolled pieces of paper containing 14 handwritten stanza's of his Ultimo Adios, Last Farewell.

(Receiver's Contextual Clue)

Rizal on 29th of December, 1896 was found guilty of establishing illegal organizations and of supporting and inciting the crime of rebellion, and is condemned to death. When he was shot, he turned his body up so that falling on his death he falls on his back, with his face to the sun.

That shot was the prelude to the collapse of the Spanish colonial empire in the 7,000 islands.

POST SCRIPT: (Now, I come back to this part.) On Nov. 14, 2010 I hopped on a train from Florence to attend Mass in St. Peter's Square, Rome. Afterwards, while waiting for a train back to Florence, a Born-Again Filipina- Italian showed me my platform and we talked. I said, I study Rizal. She perked up. She asked: Why did Rizal face up when he was shot? I was stumped. Was it because Rizal knew traitors were shot in the back, and he knew he wasn't a traitor?, I asked. She replied emphatically" 'NO. that's not the real reason. "The real reason was that Rizal at his last breath became a Born-Again Christian, he died facing God.

- Stay with me. In my next blog, I scan original engraved pictures of Manila during Rizal's time. I scoured Madrid's antique underworld (Calle Huertas) to get engravings of early Manila pictures never shown before.

Friday, December 31, 2010

How to face a firing squad execution with a normal heart beat: Rizal, 30 December 1896

[

Every time I visit my primary physician at University of California, San Francisco, I always register numbers above my normal blood pressure. Why? Because the anxiety that I will get caught up with my transgressions (lack of exercise, eating sloppy junk food) will verily pump up my blood pressure. Suppose I have to face a firing squad at dawn even if I'm convinced I'm innocent of a rebellion against the colonial government, will my blood pressure spurt up? Surely, who won't?

Every time I visit my primary physician at University of California, San Francisco, I always register numbers above my normal blood pressure. Why? Because the anxiety that I will get caught up with my transgressions (lack of exercise, eating sloppy junk food) will verily pump up my blood pressure. Suppose I have to face a firing squad at dawn even if I'm convinced I'm innocent of a rebellion against the colonial government, will my blood pressure spurt up? Surely, who won't?

José Rizal didn't.

How? By letting go.

|

| Execution, Dr. José Rizal, Bagumbayan, Manila, 30 Dec. 1896. |

When? His last 24 hours. He wrote several letters on 29. December, the day before his execution. I highlight and underline trigger words that maintain quietude and equilibrium in terms of letting go and thus lowering his blood pressure. The day before his execution, he used words about peace, tranquility and of dying with a clear conscience. He was preparing himself for the inevitable by talking about it.

29. December 1896.

His first letter was to his friend Ferdinand Blumentritt, followed by his letters addressed to his family, his brother Paciano, and to his parents, brothers and sisters.

Professor Ferdinand Blumentritt

My dear brother:

When you receive this letter I shall be dead . Tommorow at seven, I shall be shot; but I am innocent of the crime of rebellion. I shall die with a tranquil conscience. Farewell, my best and dearest friend, and never think ill of me.

Fort Santiago, 29 December, 1896.

José Rizal

PS.

Regards to the entire family, to Sra. Rosa, Loleng, Conradito, and Federico. I leave a book for you in remembrance of me.

[WOW! I'm totally intrigued with this letter. True to form, he writes: "Farewell, I'll be dead. " Then as an afterthought, he adds a Post Script (PS) sending his regards to the members of the Blumentritt family.]

[In all his earlier correspondence to Blumentritt, he always end his letters with special mention to the members of the family. Now, in his final good-bye, he ends his letter with "Never think ill of me," and signs his name. But wait, he forgets the special mention to the kids and the wife. So he adds a CODICIL to his LAST letter. My personal lawyer, Rodel Rodis, Esq. will love this. ]

[The book he sends Blumentritt is actually an earlier book sent to him by Blumentritt on which José Rizal annotated and wrote some marginal comments.]

To My Family:

I ask your forgiveness for the pain I cause(d) you, but some day, I shall have to die and it is better that I die now in the plenitude of my conscience.

José Rizal

Mr. P. R.

My dear brother,

It has been four years and a half that we have not seen each other or have we addressed one another in writing or orally. I do not believe this is due to lack of affection whether on my part or yours but because knowing each other too well, we had no need of words to understand each other.

Now that I am going to die, it is to you I dedicate my last words to tell you how much I regret to leave you alone in life bearing all the weight of the family and of our old parents!

I think of how you have worked to enable me to have a career. I believe that I have tried not to waste my time. My bother: If the fruit has been bitter, it is not my fault, it is the fault of circumstances. I know that you have suffered much because of me. I am sorry.

I assure you, brother, that I die innocent of this crime of rebellion. If my former writings had been able to contribute towards it, I should not deny absolutely, but then I believe I expiated my past with my exile.

Tell our father that I remember him, but how? I remember my whole childhood, his tenderness and his love. Ask him to forgive me for the pain I cause(d) him unwillingly.

Your brother,

José Rizal.

Dear Parents, brothers and sisters:

Give thanks to God that I may preserve my tranquility before my death. I die resigned hoping that with my death you will be left in peace. Ah, It is better to die than to live suffering. Console yourselves.

I enjoin you to forgive one another the little meannesses of life and try to live united in peace and good harmony. Treat your old parents as you would like to be treated by your children later. Love them very much in my memory.

Bury me in the ground. Place a stone and a cross over it. My name, the date of my birth and of my death. Nothing more. If later you wish to surround my grave with a fence, you can do it. No anniversaries. I prefer Paang Bundok.

Have pity on poor Josephine.

José Rizal

[WHOA: Hold it! Did we miss something here? In Rizal's last instructions, be said, No anniversaries. I take this to mean he did not want to celebrate the anniversary of his execution. Hear that? He wants us to celebrate his birthday, not his death anniversary. Let's make sure we remind people and the government this last dying instruction.]

[He preferred to be buried in the humble municipal cemetery, Paang Bundok (at the foot of the mountain) between the North Cemetery and the Chinese Cemetery. But, it was not to be. He was buried in Paco Cemetery. However, on 30 December, 1912, his remains were transferred to the base of the Rizal Monument erected in Luneta, very near the place where he was shot.]

At 6:00 am. 30 December, before marching off to Bagumbayan, (now Luneta Park) Rizal wrote:

My most Beloved Father:

Forgive me for the pain with which I repay you for your struggles and toils in order to give me an education. I did not want this nor did I expect it.

Farewell, Father, Farewell.

José Rizal

Then he took another piece of paper and wrote the exact hour of the day and addressed it thus:

6:00 o'clock, morning, 30 December, 1896.

To MY very beloved Mother, Dña Teodora Alonso.

José Rizal.

[This final letter, addressed to his mother, was pregnant with un words... only the hour and date were registered. Imagine what a calming effect this must have had on him.

To his very beloved mother, he emotionally left his beating heart. Words could only serve unworthy of that sacred silence--that special channel where a mother and son can communicate at a supreme higher level. That empty page was symbolically full and finally he did let go.

When the military physician took his pulse before his execution, he had a normal heart beat.

Saturday, December 25, 2010

José Rizal greets you a "Merry Christmas" in a letter dated, 10 Dec. 1891.

I had religiously read and re-read José Rizal's letters to his parents, brothers and sisters in the Philippines and to his good friend Ferdinand Blumentritt of Lietmeritz, Austria. It is a daunting experience. Taken in current contemporary times, it's like Rizal was blogging and I was a blog follower. There are several volumes printed in 1961 by the National Historical Institute, National José Rizal Centennial Edition.

At that time, the mail boat schedule was announced and posted in all municipal offices. If one wanted a letter to be posted for abroad, it had to make the deadline. It took forty to forty-five days for the steam boat to and from the Philippines. Fortunately, a mail boat left every week.

Since he started writing his letters to his family, these letters had taken on a life of a travelogue. He wrote about his observations and his thoughts and even his dreams while aboard the ship through Suez Canal, stopping in Naples, Italy, then docking and weighing anchor at Marseilles, France, From there he took the express train to Barcelona, Spain. He wrote about the difference between the courteousness and politeness of the French border patrols and the coarse bullying of the Spanish border guards.

Rizal instructed his sisters that they should save his letters addressed to "My dear parents, brothers and sisters," because he planned to compile all these letters when he got home from studies abroad. I'm so glad that the Rizal family saved all his letters. Others had pages missing but in spite of that I can get a glimpse of the José's unique characteristics and persona as a young adult being acculturated to Madrid's social life. I particularly like the fact that he goes to theaters and occasionally to "bailes". Pero na mimintas siya.

Once, he wrote about going to Alhambra, a dance hall. It was a masquerade ball and he went with friends. Of course, they oogled the girls. Soon three young girls floated by. What attracted Rizal was the fact that they were wearing the Filipino dress. Let's read what his observations were.

"11 January 1883.

There we saw (and they attracted the attention of everybody in the theatre), three young women wearing very elegant Filipino dresses, one with tapis and the others without it. Although I suppose they didn't know how to wear it (namintas pa--he makes some criticism. pvf.) as well as the true daughters of Malate, Ermita, Sta. Cruz and Binondo, for only two of them were Filipino women; nevertheless, they seemed to us, divine and elegant. They walked about dragging along their shirts of bright red and white, yellow and white, violet and white, topped with jusi blouses, piña neckpieces that everybody stared at them."

In the spirit of Christmas and the New Year, I tried to find out if he greeted anybody a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. He actually did, in a letter to Ferdinand Blumentritt written in German and dated 10 December, 1891 Hongkong. See facsimile of his letter below: On top of the page, he writes, "Merry Christmas."

What a lovely and charming way to greet you all a Merry Christmas *Weihnacht* straight from Rizal's own holiday greeting, and to top it all, in his own penmanship.

"

At that time, the mail boat schedule was announced and posted in all municipal offices. If one wanted a letter to be posted for abroad, it had to make the deadline. It took forty to forty-five days for the steam boat to and from the Philippines. Fortunately, a mail boat left every week.

Since he started writing his letters to his family, these letters had taken on a life of a travelogue. He wrote about his observations and his thoughts and even his dreams while aboard the ship through Suez Canal, stopping in Naples, Italy, then docking and weighing anchor at Marseilles, France, From there he took the express train to Barcelona, Spain. He wrote about the difference between the courteousness and politeness of the French border patrols and the coarse bullying of the Spanish border guards.

Rizal instructed his sisters that they should save his letters addressed to "My dear parents, brothers and sisters," because he planned to compile all these letters when he got home from studies abroad. I'm so glad that the Rizal family saved all his letters. Others had pages missing but in spite of that I can get a glimpse of the José's unique characteristics and persona as a young adult being acculturated to Madrid's social life. I particularly like the fact that he goes to theaters and occasionally to "bailes". Pero na mimintas siya.

Once, he wrote about going to Alhambra, a dance hall. It was a masquerade ball and he went with friends. Of course, they oogled the girls. Soon three young girls floated by. What attracted Rizal was the fact that they were wearing the Filipino dress. Let's read what his observations were.

"11 January 1883.

There we saw (and they attracted the attention of everybody in the theatre), three young women wearing very elegant Filipino dresses, one with tapis and the others without it. Although I suppose they didn't know how to wear it (namintas pa--he makes some criticism. pvf.) as well as the true daughters of Malate, Ermita, Sta. Cruz and Binondo, for only two of them were Filipino women; nevertheless, they seemed to us, divine and elegant. They walked about dragging along their shirts of bright red and white, yellow and white, violet and white, topped with jusi blouses, piña neckpieces that everybody stared at them."

In the spirit of Christmas and the New Year, I tried to find out if he greeted anybody a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. He actually did, in a letter to Ferdinand Blumentritt written in German and dated 10 December, 1891 Hongkong. See facsimile of his letter below: On top of the page, he writes, "Merry Christmas."

What a lovely and charming way to greet you all a Merry Christmas *Weihnacht* straight from Rizal's own holiday greeting, and to top it all, in his own penmanship.

"

Saturday, December 18, 2010

José Rizal.: The Wanna be Gentleman Teen ager

José Rizal, the Philippine National hero was once a teen-ager. The attributes of a teen is that one day they act goofy, the next, they act mature. One day they are full of pranks, the next they are full of seriousness. Often they are sentimental, at the same breath they are rational.

Ladies and gentleman, allow me to present to you Jose Rizal, the teen ager.

The first picture above is available on Wikipedia. He is 18 years old, then a pre-med student at the University of Santo Tomas, where he made a name for himself by being a serious student, having won numerous prizes in arts and letters. Rizal made a sketch himself. It was a picture of a young man, a teen.

He went to Europe in 1882 when he was 20. He was gregarious as a post-teen ager, traveling alone first class, on a steamship bound for Europe for the first time.

He touched Spanish soil (Barcelona) first week of June. As a young adult, he was full of himself. At the Fonda de España (inn) in Barcelona, he disdained its shabbiness, comparing his privileged life in Calamba with all the landed gentry amenities. At this time, he immediately went to work. He submitted an article published in Diariong Tagalog. It was a treatise on patriotism.

He ran out of money and went to the Jesuit college where he presented letters of introduction. Here he roomed with old and retired Jesuit priests. He begins his teen age characteristics again by making opinionated statements like "the old priests were speaking a "rude" language." It never occurred to him they were speaking in Catalan. He was of course comparing the Catalan language to the flowery and smooth style of the Castillian language that he learned to perfection. He was 20 going on 30 at that time.

He proceeded to Madrid in September. Now he had reached the ripe old age of 21. He joined the Circulo Hispano-Filipino, whose members were Filipino students studying in Madrid including a few Spaniards who were born in the Philippines--the Insulares.

In self-righteousness, he dissolved the Club's newsletter because the submission deadlines were never met. He forbade his friends to gamble away their time in ""useless" card games. In a spirit of prank, he conferred on his room mate, Vicente Gonzalez, (an old classmate from Ateneo de Manila days) the monicker: Marquis de Pagong (Marquis, The Turtle). Vicente was just being Hispanized, staying late for dinner up to the wee hours of the morning and of course would be sluggish, while Rizal would be up at 5:30 in the morning, bright and spanky.

He met Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, the painter. He sat for an oil painting. It is the 2nd picture above. Resurreccion captured the teen-aged José Rizal. Felix is the consummate interpreter of character nuances. This is my favorite Rizal portrait....impish, rakish grin, tousled hair--which he tidies most of the time--off-skilted tie, twinkling eyes as if contemplating on doing something silly: in general, of being such a charming teen-age matinee idol.

Felix brought this oil painting to Manila and presented it to Don Antonio Rivera, Rizal's uncle and Leonora Rivera's father. Visitors came to admire the artist's signature, not the image. It was after all signed by a Resurreccion. Paciano actually glossed it over. Only later, when viewing from afar, that the resemblance to his own brother struck him. Paciano had actually forgotten the image of a young teen-ager. All this time, he was projecting the aura of Jose Rizal as a Europeanized medieval gentleman: the ilustrado: upright and proper (in his cuerpo (Rizal never wore an overcoat, but was dressed in the impeccable European style frock coat).

The artist in his painterly manner, gave us the humanized young essence of Rizal seldom brought out by our Rizalist scholars who want to present to us an intellectualized Rizal forgetting that like our own teen-aged offsprings and sibings, he too went through the process of teen-aged ambivalence as he was training to be the Great Hero that he had become.

x

Stay with me in my next blog where I present José Rizal in Madrid as The Ma-pintasin: The critic.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Dr. Penelope V. Flores' Presentation of the places and areas connected to Dr. Jose Rizal, Madrid, Spain (1882-1887)

Related articles

- Jose Rizal monument in Spain vandalized, says tourist (globalnation.inquirer.net)

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Noli me tángere translations

Jose Rizal and Juan Luna at El Prado Museum, Madrid, 1884.

Jose Rizal and Juan Luna at the El Prado Museum, Madrid 1884

Thanks to King Carlos V and his son Felipe II, the Prado has the world’s top collection of Titians. Equally rich is its Rubens collection, and the Prado also has a rich collection of Italian paintings of the Romantic, Mannerists, and Baroque periods. King Felipe IV and Velásquez had a rewarding art history relationship (Alcolea, 1991: 227). Felipe commissioned Velásquez to travel all over Europe to buy paintings on his behalf. Twice Velásquez toured the continent for this purpose. Many of the choice works in the Prado are there because in riding back and forth between Italian cities, Velázquez came upon canvases, which he thought the king might like. It is safe to assume that Velázquez given a blank check by King Felipe to purchase his favorite paintings for the king, the Italian collection in the Prado were Velásquez’ personal choices.

The Spanish Masters

On many occasions, Rizal and Juan Luna, the Filipino painter, a student of Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, would have sauntered over to the Prado Museum to feast their eyes on contemporary art and to study the Spanish masters.

Only that year (1884) Juan Luna’s large oil painting Spoliarum won the prestigious Madrid National Exposition of Fine Arts award. This young Filipino compatriot proved himself as an “international artist.” Luna medaled gold! Luna’s entry showed the fresh corpse of gladiators being dragged across a dungeon floor of the Coliseum.

|

| Spoliarium by Juan Luna |

His fame assured, Luna would be commissioned to paint the Battle of Lepanto specifically for the Spanish Cortes Senate Assembly hall.

The Battle of Lepanto by Juan Luna can be seen at the Senate Hall, Madrid.

|

| The Battle of Lepanto by Juan Luna |

Another Filipino artist, Felix Resurrección Hidalgo garnered the silver medal for his Las Virgines Cristianas Espuestas al Populacho, dramatizing the humiliation of Christian women at a Roman slave market. To Rizal, who gave the toast at a celebratory party for the double victory, Luna’s fallen fighters and Hidalgo’s slave women were veiled allegories of the Filipino people’s suffering from Spanish political repression.

|

| Cristianas Espuestas al Populacho by Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo |

“They proved to the world “indios” could, despite their supposed barbarian race, paint better than the Spaniards who colonized them (Ocampo, 1990: 63.)”

Both had beaten the Europeans at their own game in a major art competition by demonstrating their mastery at painting historical subjects in the grand mannerist style.

Empathetic Fallacy Conversation

What could it be like if we eaves-dropped on the Rizal and Luna conversation on the gallery floor of El Prado? We have no proof that this conversation occurred, but we have no reason to believe that the conversation could not have taken place either.

The two Filipinos stand before Velasquez’ Las Meninas (Maids of Honor, or The Family of Philip IV, 1656).

|

| Las Meninas by Velasquez |

Rizal: I can read it pretty well. The center is the little princess. The other subjects recede into the background giving an interesting perspective.

Luna: You mean the Infanta Margarita Teresa.

Rizal: Yes, the maids are clustered about the Infanta, her tutors, page, and dwarf in attendance, and her huge dog is in the foreground. From the dog, we work our eyes up by stages to the distance. Velasquez paints himself into the picture. What an idiot!

Luna: Remember, Velázquez was always concerned about his status as a court painter. Therefore he must show himself to the king and queen in his creative art. See that mirror? That is the reflection of the king and queen. Can you see the two huge Rubens in the shadow?

Rizal: Yes, I can see it now, obliquely.

Luna: Here is the whole world of the inner court, presented in reverse order of importance. It portrays a single snapshot moment of each figure responding to the unannounced entrance of the king.

They view Goya’s King Charles IV and his Family (1800)

|

| Charles IV and Family by Goy |

Luna: Goya shows real beauty with cruel ugliness in this picture.

Rizal: Beauty in its ugliness? Is that a dramatic idiom?

Luna: Yes. Goya portrays the royal family as vain and pompous in the illusionist sense.

Rizal: Oh, you mean the dazzle of the silk and lace? But where is the illusion? I see an infinite delicacy with which the ribbons, jewels and sashes glitter.

Luna: That’s exactly my point. The painter patronizes their glamour. See how the royals are spread out like a frieze, heavy, dull and self-absorbed? He shows how remote they are from the people. If you can portray the glitter of life and imbue it with folly without shoving it in one’s face, that to me that is real beauty.

Heightened Consciousness

While my characterization of the scene between Luna and Rizal is in the fictionalized narrative style, yet here are two young Filipinos (Rizal in 1884 just celebrated his 23nd birthday), non-Spaniards experiencing art, discussing aesthetic issues and conversant with the western art world’s vocabulary of heightened consciousness in El Prado Museum. That in itself is a rarity.

Understanding art in an amazing process. The more one studies it, the more it forces one to look at embedded references and nuances. Gardner, in Art through the Ages (1980) explains this methodical pursuit of a system as "bringing order to visual experience.” Not anybody can get access into this kind of experience and use of language. Rizal most especially was among these selected few.

Noteworthy too is the fact that the expatriates in Madrid of the time were being acculturated into the European milieu, implying a level of facility and comfort level with Western thought without losing their own cultural identity. Art appreciation necessitates an intellectual process made more significant in Rizal’s case because it requires an access to education, and into the power of symbolic interactionism.

Looking at paintings is a gut reaction. Either you love it or you hate it. That Rizal, Luna and their compatriots understood the references, subtleties, and symbolism in a painting show they had penetrated into that higher closed circle of the transformative power elite.

Saturday, August 28, 2010

The Many Translations of José Rizal's Noli me tángere

Last on my blog series on the title Noli me tángere

“Dicit ei Iesus noli me tangere nondum enim ascendi ad patrem meum.”

Jesus saith unto her, touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father.”

Rizal took the title of his first novel from the Gospel of St. John, Chapter 20, line 17 (King James Version. London: Robert Barker, 1611). It was most likely that he was led to this particular quote because on one of his visits to the El Prado Museum in Madrid, he chanced upon the impressionable Correggio mannerist style painting named Noli me tángere, (see my blogs, August 26, 27, 28).

Leon Maria Guerrero writes in his translated volume of Noli me tángere: “The words are taken from John XX, 17, and are spoken by the risen Christ to Mary Magdalen, but the subject would seem to have no connection with the Rizal story,” (1961, xv). I tend to agree with Guerrero. As far as the story’s plot and characterization, it is not a description of the novel. However, as a metaphor and an allegory for a society’s social conditions, it makes sense. Rizal has a tendency to use metaphors and allegories in his writings.

The late monsignor Knox, in his translation of the Bible into modern English, renders Touch me not as Do not cling to me thus. He is right. Chapter 20 from my bible copy (The New American Bible. St. Joseph edition. 1970: 137-138) says: Do not cling to me. However, on the commentary below the page, it says. Don’t touch me is the literal translation. However, there is a profoundly spiritual aspect to this literal statement.

Let me explain. Mark, Chapter 28: 9 refers to the women who visited the empty tomb. When they see him risen from the dead they approached and were about to take hold and cling to his garments in order to anoint his feet and body, as was the Jewish custom in those days. Jesus addresses them saying: I have not yet ascended. In Mark, he doesn’t say, Don’t touch me. It’s implied. Like “Wait, I’m going first to my Father and when I come back imbued with His Spirit, then you can touch me with your traditional anointing rituals.”

For John and many of the New Testament evangelists, the ascension to heaven is understood in the purely theological terms. Resurrection means going forth to the Father to be glorified. The interaction with Mary Magdalene in the John scriptures dramatizes such an understanding. Rizal, who is so metaphysical in his letters and his description of his life in Madrid, understood what it meant to be imbued with the Spirit of reform before he can preach to his countrymen.

Noli me tángere is not Spanish nor Italian, but Latin. At that time, Latin was the language of the enlightened. In fact the Italian dialect of Florence used by Dante and Boccaccio was considered “vulgar.”

On the several title forms

The Noli has been translated many times into many languages almost from the date of its publication. However, since I began my search on where the idea of the book’s title must first have originated, I end with how the book’s title was finally translated.

In the Filipino language translation by Bartolome del Valle, Benigno Zamora and Salud Enriques, (Philippine Book Co. 1993 edition), the title is not translated into Filipino. The original Noli title is retained.

Charles Derbyshire’s translation in 1912 was entitled The Social Cancer.

In Leon Maria Guerrero’s original translation, (1961) his title was The Lost Eden. In Guerrero’s later edition, 1995, the title is Noli Me Tangere: He writes: "I did not find it wise to translate the title, "(p xv.)

The translation by Maria Soledad Lacson-Locsin edited by Raul L Locsin (1996) used the facsimile of the original cover.

The translation of Harold Augenbraum (Penguin Classics, 2006) shows the Rizal original cover. It also had a subtitle Noli Me Tangere, and in parenthesis Touch Me Not was inserted below the first line title.

Of course here in my blog I use the Spanish style consistently for the title: only the first word is capitalized, and there is an accent on the ain the word tángere.

In closing, I would like to confess to a trivia observation that escaped me at that time. As a Rizaliana student in college very few of us, especially myself, never picked up this hidden and transparent fact. I must have been dozing during that lecture. In 1889, Rizal submitted a satirical article published in Barcelona as a pamphlet. He used a pseudonym: Dimasalang (Masalang, touch. Di is a contraction of the word hindî, the imperative of don’t).

In the end, Rizal himself had advanced the Tagalog translation of Touch me not. It was Dimasalang, also his symbolic Masonic name.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/The_Social_Cancer_1912_cover.jpg/300px-The_Social_Cancer_1912_cover.jpg

http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51aFHQxVRnL._SL300_.jpg

Stay with me on my next blog: José Rizal and Juan Luna at the El Prado Museum, Madrid.

Related articles by Zemanta

Friday, August 27, 2010

In Search for a Book Title: Rizal’s and Correggio's Noli me Tángere. Part 2.

In Search for a Book Title: Rizal’s and Correggio's Noli me Tángere. Part 2.

Noli me Tángere, 1534. Panel transferred to canvas, 130 by 103 cm.

Prado Museum, Cat. No. 111

(To find Correggio at Prado Museum, you must go to the ground floor and look for the 16th century Italian Renaissance painters.)

Correggio’s Noli me Tángere’s canvas is deeply poetic. His risen Christ imbues a deep sad tone, painful irony, and wavering color tones, with a soft simmering beauty of the flesh. Rizal must have been able to trace the effect of Correggio’s poetry: the interplay between the ardent Mary Magdalene, all rich and spreading drapery and the austere Christ, who withdraws from her with infinite courtesy. With outstretched arms, Christ almost dances in the freedom of resurrection while Mary is recumbent with the heaviness of earthly involvement. A tree tells us that newness of life had only just begun and a great world stretches away toward the hills, remote, witnessing, and leaving Mary Magdalene to her own choices. There is a touch of loneliness in the picture. But fundamentally, the mood of the picture has an earthly vigor.

In his novel, Rizal was beginning to express Correggio’s romantic and mannerist style in his writing (mannerist: meaning greater depth in spiritual insight) in terms of dignity and realism. Correggio shows superb skill in showing the truth about the situation with all the attendant weaknesses. And yet he produced a picture that is supremely beautiful.

Noli me Tángere…now Rizal must have been sufficiently challenged and motivated. His brain must have worked on overdrive. He probably would have gone back again and again to the Correggio at the Prado. Rizal must have talked to himself thus:

“The use of symbolism and nature is evident in the Correggio’s Noli me Tángere. The rich brocade cloth of the Magdalene dazzles and shimmers in the light, the red almost bleached out, like the plumage of a bird. The other figure in the panel creates an undercurrent of violence and pain, with open outstretched hands, the image of Christ arises almost simultaneously, the look of expectancy, unafraid, unprotected”.

At this moment in time, in Rizal’s mind, as in an epiphany, Correggio’s Noli me Tángere and his novel no longer were parallel forms. These had merged as one.

Is this Too Hard to Believe?

Up to this point, my research on searching for how Rizal got the idea for a book title had all been conjectures. I knew that a Titian and a Correggio painting with the title Noli me Tángere existed. Titian’s Noli is kept at the National Gallery in London, while the Correggio one remains on permanent exhibit at the Prado.

My own curiosity aroused, I had to see the Correggio painting for myself. I packed a Carry-On and booked a flight to Madrid. At the Philippine Embassy in Madrid, Jaime Marco gave me a tour of the places where Rizal lived. Jaime wrote a monograph “Rizal’s Madrid. ” At the Prado I asked permission to take a photo of Noli me Tángere painting.

Incredible as it may seem, many of us Filipinos who had read the novel were never cognizant of, nor had even been made aware of this painting that left an imprint on Rizal’s creative genius. Of the many historians, writers, authors, and scholars writing about Rizal, none had made this connection, and if they did, this fact was never brought explicitly to our attention. In discussing my conjecture with an imminent Philippine historian and author, she confessed that she had been to the Prado many times, but was never aware of this Correggio painting.

It is fitting that Filipinos should plan to have this painting included in their repertoire of Rizaliana teaching materials. In addition it ought to be an important itinerary in Rizal’s Madrid: Walking and Cultural Tour, promoted by the Philippine embassy in Madrid.

The Smoking Gun

My conjectures at this point were inconclusive. I needed a confirmation, a citation, to assure me that my proposition about the Rizal-Correggio connection has some merit.

Then out of the stack of texts, correspondences, documents, and writings, I came upon an Austrian book in German written by Harry Sichrovsky, the foreign editor of Austria’s Radio and TV service specializing on China, Korea, and South Asia. The book is entitled Der Revolutionär von Leitmeritz: Ferdinand Blumentritt und der Philippinische Freiheitskampf (1983).

Buried amidst the voluminous Rizal-Blumentritt correspondence, I found the “smoking gun.” In one seemingly unprepossessing sentence, at the bottom of a long expository paragraph explaining Rizal’s Noli me Tángere in the context of the word spoken by Christ to Mary Magdalene, Professor Sichrovsky wrote as if in afterthought:

“Rizal had seen in the Prado Museum in Madrid the famous painting of Correggio, which depicts the scene.” English translation, 1987, p 38. (Highlight and Underscoring mine.)

There it was staring right in my face—inconspicuous, nothing less, nothing more—no extraneous explanations, no sleuthing suspense, and no genuine illumination to any reader either. It was an overlooked artifact, except where my persistent questioning mind was concerned.

Philippine scholars had never connected the dots because it was an unlikely source. They were looking at rationalizations in written sources when looking at an art museum where our hero frequented would have given them a really important and significant clue.

The Final Answer

Rizal himself answers the final question. For those who seek original sources, there is a letter dated March 5, 1887 at the Ayer Collection of Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois. Written in French, Rizal explains why he chose to name his novel Noli me Tángere. It is a rationalization. Rizal was in Berlin at that time and studying with a French teacher, Madame Lucie Cerdolle. Marcel Colin, a French Rizal scholar translated this letter for me. He wrote on the margin “Rizal’s French wasn’t perfect, but he could manage very well in our language.” (Correspondence, 5-23.87).

Rizal held the mirror to the Filipino people of their own situation. There was an incredible phobic feeling for the title “Do not touch me”. No one would speak of the human vanity, vice and hypocrisy during the colonial period as Rizal did. He was the voice of the people.

Guadalupe Fores-Guanzon (1973) explained this kind of feeling in her introduction to the English translation of the La Solidaridad.

There was an upsurge of nationalist feeling among the Filipinos, many of whom awoke to the realization that Spain’s colonial administration in the Philippines could no longer be suffered in silence, for in many respects, it was arbitrary, unjust, graft-ridden, and largely dominated by the friars (p vii).

According to Leonard Casper (1966), a literary critic, Rizal’s burden was to startle into imagery the Philippine presence beyond all question of human worth (p 18).

As Yabes (1963) pointed out, Rizal was always the realist, who in the Noli kept truth and its consequences ever present in his mind.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)