On Dr. José Rizal’s 150th Birthday Anniversary

Guest Speaker: Dr. Penélope V. Flores

Oakland Asian Cultural Center

June 18, 2011

Special Guest Mr. Tom Consunji, a Rizal Descendant, Philippine Consul General Marciano Paynor, Jr, Ladies and Gentlemen, friends:

Please enjoy the wonderful Dr. José Rizal Exhibit at this Oakland Asian Cultural Center. It opens today free to the public until August 31st 2011.

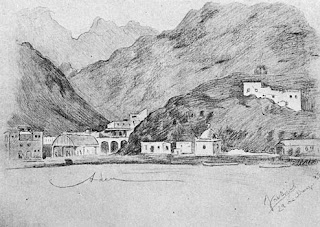

San Francisco Bay Area, California is fortunate because Dr. José Rizal came here on our shores in 1888. His steamboat arrived from the Philippines via Yokohama, Japan. His ship anchored and was processed by Immigration officials on Angel Island. He got off at San Francisco's Pier. He billeted himself at the Palace Hotel on Montgomery Street. (Today, there is a historical marker displayed there.) Then, he took a ferry to the train terminal station, right here in Oakland, purchased an overland transcontinental ticket all the way to New York. From New York, he boarded a steamship and sailed across the Atlantic where he landed in England. (See the large World Map of Dr. Jose Rizal’s Travels in the exhibition hall 50 x 60 inches, mixed media.) He stayed in London from 1889 to 1890 and completed his research at the British Museum Library that produced his Annotated Volume of Antonio Morga’s Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas.

My participation in honoring Dr. José Rizal’s 150th birth anniversary is not dictated by patriotism. It is more than that. It is personal.

First, let me ask for a show of hands. How many of you read Rizal’s famous novel NOLI ME TÁNGERE? You read it in high school under duress because it was required reading, right? Suppose I tell you that it was almost kept hidden away because Rizal had no money to have it printed? His allowance from home did not come regularly due to many dismal and unexpected economic turns.

It was 1886. Rizal was editing the final NOLI manuscript in Leipzig, Germany, when an old Filipino pal arrived from Barcelona, Spain. Like Rizal, he was a newly minted physician. Rizal showed this friend the manuscript, regretting that printing will have to wait because he had run out of funds. His friend flipped through the pages. It was a glowing piece of work. He was impressed and enthralled.

He asked for the printing cost. “Three hundred pesetas,” was the reply. His wealthy friend said, “Let me give you the money to print this seminal work.” This friend was Dr. Máximo Viola. He was my grand uncle: my grandmother Juliana Viola’s eldest brother.

One would think that Rizal would find this offer providential. But, sad to say,Honorable Senõr Don Tomas Consunji Lopez Rizal, your great, great, grand uncle José Rizal was a real basket case. Why? His Amór propio was as thick as molasses. His heightened sense of pride and hurtful dignity was as high as Mt. Apo--the highest peak in the Philippines.

No, he was not accepting any monetary gift, most especially if he never asked for it.

But my grand uncle knew Rizal better than Rizal knew himself. He insisted. “Peping,” he smoothed it over, “It’s just a loan. Repay me whenever Paciano’s money arrives.”

So the two friends scouted around for the cheapest printing shop. They found a printing press manned (womanned) by widows and orphans called the Guild School of Typesetters: Berlin Book Printing Press. And the presses went rolling and by March 1887 2000 copies were ready for distribution.

There’s always something fishy whenever the Philippine Department of Education textbook division writes Rizal’s biography. After the statement that Dr. Viola lent Dr. Rizal money, the next sentence that immediately follows is that Rizal paid it off. It's too obvious. Something else was going on. In modern lingo, it raises a flag.

When Rizal’s allowance arrived, history texts tell us he paid Viola back. That's well and done. Clean. Simple. However, persistent Viola family lore exists. The Viola version was that Maximo invited Rizal to join him on his tour of Europe and so he deftly pushed the money back to Rizal, suggesting it's perfect for the trip. And so it was that for three months (April, May and June, 1887), the friends traveled together in European capitals. They met with Ferdinand Blumentritt in Leitmeritz, Austria.

Come to think of it; how could Rizal, who had been too distraught for not having enough money to print the Noli, now could go traipsing all over the grand cities of Europe staying in big hotels and traveling first class? Virtually, Viola deflected the payment of that loan. He was a great travelling companion and friend. (Read Maximo Viola's book "I Travelled with Dr. Jose Rizal." 1913.)

Dr. Maximo Viola was one among the few Rizal friends who never had any political agenda except his enduring friendship with our national hero. He remained private even during the Philippine revolution. That's why you never heard about him.

Now, let's turn to that contestable 300-peseta loan.

I requested my accountant, to compute the amount of this debt if paid today. Mr. Vicente Marquez, CPA, of 1200 Bayhill Drive, San Bruno, California had been bitten hard by my blogspot on Dr. Jose Rizal's Noli me Tangere story. http://penelopevflores.blogspot.com/

First he wrote, "Since I do not know yet how to convert Philippine pesetas during the Spanish time into modern Philippine peso, I can only give you the future value of that 300 pesetas:

"Three hundred (300) pesetas at 3 per cent compounded annually for 125 years will be equivalent to 12,072 pesetas.

Three hundred (300) pesetas at 5 per cent compounded annually for 125 years will be equivalent to 133,593 pesetas."

A week later, Vic Marquez followed it up. Not only did he calculate the annual compounded interest (at 3% and 5% respectively) of Dr. Rizal's debt to Dr. Maximo Viola regarding the printing cost of his novel. Vic went one step further and computed the monetary value at that period in time. He did this ingeniously by pegging it to the Gold Standard.

He explained, "The Spanish currency was used in the Philippines during the 300 years of Spanish colonization. In 1869, Spain joined the Latin Monetary Union; in 1873 only the gold standard applied. According to this standard, one peseta is equal to 0.290322 grams of gold."

Aha! Now we have a stable and absolute measure. Let's do the math.

In today's dollar, one gram of gold is equal to US$39.90. If Maximo Viola's peseta is equivalent to .290322 grams of gold, then I think we can express your 12,072 pesetas x .290322 x 39.90 =US$139,840.33.

We chose to use the 5% interest compounded annually for 125 years--for we should always calculate to our advantage-- so his 133,593 pesetas x .290322 x 39.90=US$ 1,547,521.11."

So, I say this evening to our special guest, a Rizal descendant sitting among us in this hall: “The Most Honorable and Distinguished Rizal descendant, Señor Don Tomas Consunji Lopez y Mercado Rizal, with all due respect, I have something for you. Here’s a bill for a million and a half whooping dollar debt you owe the Dr. Maximo Viola descendants represented today by Penelope Flores Villarica y Viola. (Note: I follow the Spanish naming system of indicating my father's (Villarica) mother's maiden name, Viola.)

I bet that of ALL the celebrations occurring simultaneously all over the world on the 150th anniversary of Rizal’s birthday, this one in Oakland, CA is the MOST unique and compelling event that will be remembered for another 150 years.

I wish to congratulate Jim Espinas of FACES, Herna Cruz Louie of ACPA, Oakland Asian Cultural Center, and Philippine Consul General Mariano Paynor, Jr. of San Francisco, California for making this happen.

Especially to James, I salute you. You are a treasure. Thanks for organizing this event and curating the exhibit. Thanks for providing the opportunity of reliving the Rizal /Viola connection and sharing it with all of you this evening. THANK YOU.